I was driving with my friend D the other day having one of our discussions. We rambled on topics ranging from our kids, to politics, to old friends, to myriad other subjects as we are wont to do, until we finally landed on something having to do with some church’s ongoing project.

“I know you’re allergic to anything having to do with religion,” D said, “but still, this seems overall good for the community.”

I rolled my eyes. “My one regret in life,” I responded, “was not having two daughters so I could name them Anna and Phalaxys.”

D looked at me without speaking.

“Then I could take them to places like churches and synagogues and mosques and…I don’t know, some far-flung mountain-top tableau with a lone guy meditating on it, and say, “I’m sorry, but your antics are causing my children to have a reaction.”

D’s expression didn’t change.

“Or maybe, ‘Gee, I’d love to come in, but you know…’ and then I’d wave vaguely at the girls.”

“You’re ridiculous,” she said.

“No,” I said, “saying ‘You’re ridiculous’ would be too obvious. Besides, that’s what I do now, and people call me intolerant.”

“Well you are intolerant,” she said.

“I mean, yeah,” I said, “But I’m also right.”

She sighed. I looked at her.

“I guess I could just get two cats.”

D put her head in her right hand, her elbow against the car door.

“Hi, these are my cats Anna and Phalaxys. They’re rescues. Ooh! The cool thing about that would be they’d not only be it, they could cause it!”

Then we went shoe shopping. Occasionally I’d drop one shoe on the floor in front of D, look at her, say, “Anna,” then drop the other and say, “Phalaxys.”

Dreams of naming children for a purpose is a family tradition. While I was somehow “accidentally” named after my grandmother Joan’s only despised sister, my father has always bemoaned the absence of a son in his life he could name Pubert. Why? No clue.

He wished for me to have at least one daughter so that I’d name her Alopecia, which he thinks is a fantastic name. Instead he had to settle for Max and Jake, though they’ve been called various nicknames, mostly Thing 1 and Thing 2, their entire lives. I named them Max and Jake because of the careers I imagined they’d have with those names: Max, Private Detective; Jake, Investigative Reporter.

That they are a professional climber and a scientist, respectively, is fine if you like that sort of thing. But they won’t let me change their names, which seems unfair. It should be Brant, Professional climber. Or Cliff. That’d be hilarious. And Albert, Scientist. Or maybe Galileo, if he wanted to be showy.

I’d been counting on nominative determinism to kick in when I named the boys. It’s the theory that people tend to gravitate towards areas of work which reflect their names. I can’t believe it didn’t pan out.

The term was coined in 1994, when New Scientist Magazine’s Feedback column noted several ongoing studies being carried out by researchers with fitting last names; a book on polar explorations by Daniel Snowman, for instance. Though the magazine has tried to kill interest in the topic ever since, they’ve failed. Year after year readers send in more evidence of this obviously factual phenomenon: An optometrist named Hugh Seymore; veterinarians named Dr. Pusey and Dr. Katz; doctors named Dr. Nurse, Dr. Blood, and Dr. Kill (he later changed his name). Stephen Sparks is a volcanologist, and Ben Winger studies American songbirds.

I myself knew a woman in a certain film genre with the name of Micky Dickoff.

And this doesn’t just affect humans. The first vertebrate to copulate was the fish Microbrachius dicki (Oldest genitals found. Went out of fashion for eons).

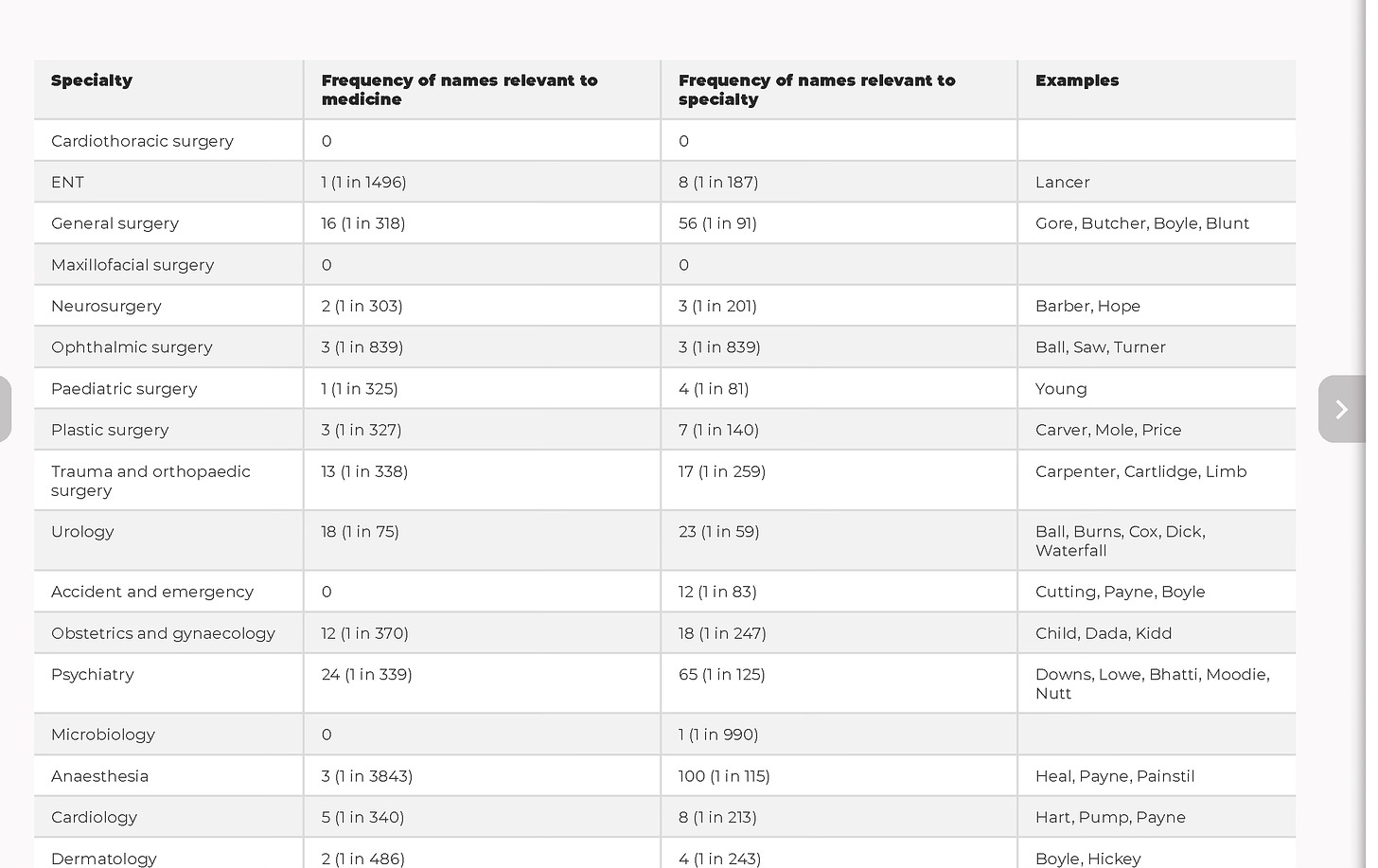

A 2015 published research paper by Limb, Limb, Limb, and Limb studied the effect of surnames on medical specialization. They looked at 313,445 entries in the medical register from the General Medical Council, and identified last names that were apt for the speciality; Limb for an orthopedic surgeon, for example, and Doctor for general medicine. They found the frequency of names relevant to medicine and to subspecialties was much greater than what could be expected by chance. “Specialties that had the largest proportion of names specifically relevant to that specialty were those for which the English language has provided a wide range of alternative terms for the same anatomical parts (or functions thereof). Specifically, these were genitourinary medicine (e.g., Hardwick and Woodcock) and urology (e.g., Burns, Cox, Ball)...”

You’d think my kids could have been a damned detective and investigative reporter. It’s not like I named them Butts and Dickoff.

The Wikipedia article on the subject discusses what the ancient Romans referred to as "nomen est omen:” the name is a sign. They briefly discuss psychologist Lawrence Casler’s proposed three reasons for nominative determinism: that self-image and expectation based on one's name creates it; that one’s name creates expectations from others so powerful that one acts on those expectations; or genetics.

Sure, if you come from a long line of judges and your name is Judge, that works, or perhaps Smith if you’re a burly type from generations of hammer-wielding blacksmiths. But what are we to assume about Mr. Lipshitz? Or Cox and Ball?

Anna and Phylaxis will leave no such doubt in people’s minds, nor will the question of nature versus nurture be germane as their names will be both cause and effect.

If you want me I’ll be off climbing a mountain with my cats. We have some annoying person we need to chase off.

Morning Aquatistism

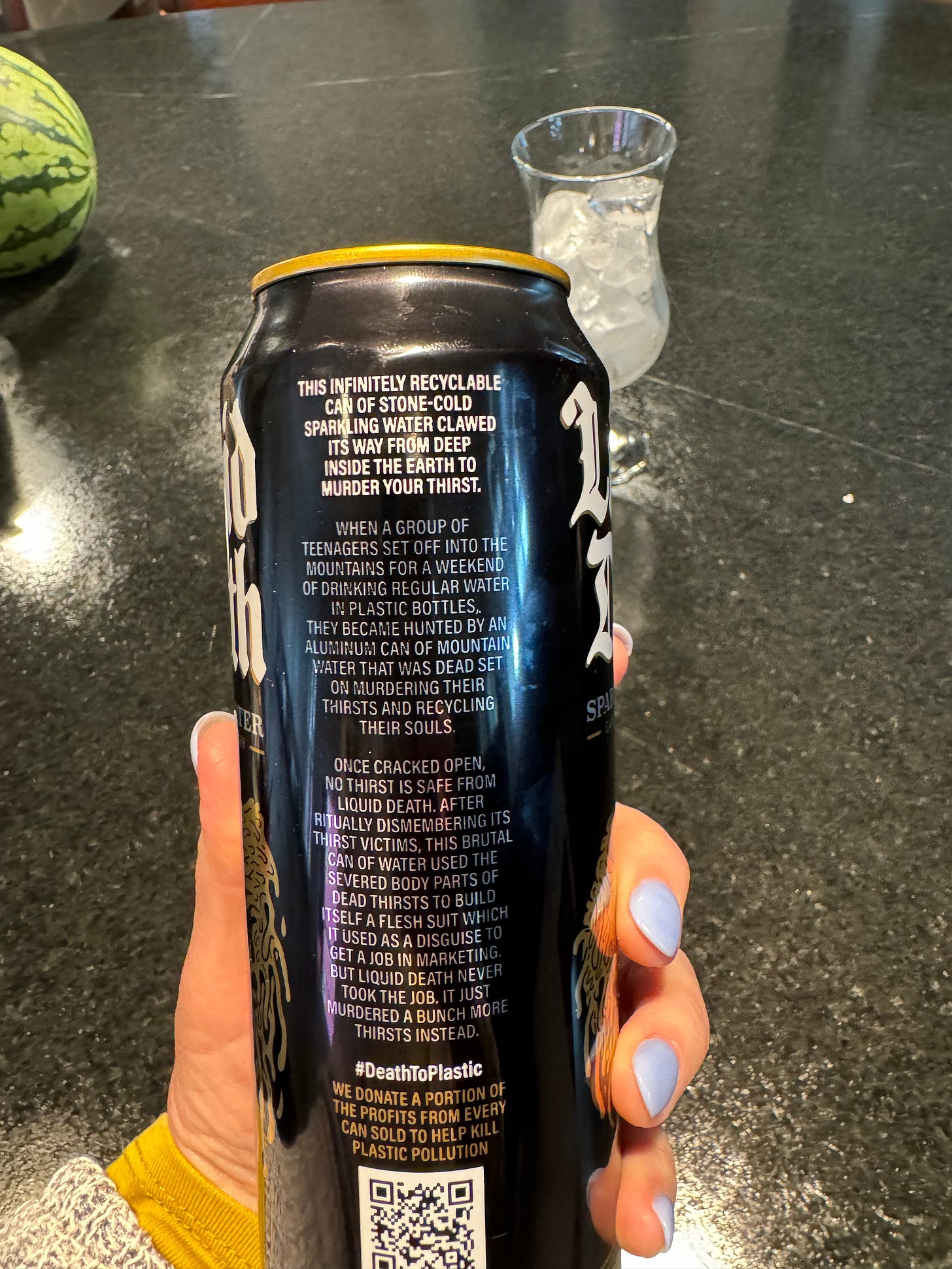

As D and I were grabbing some end-of-day supplies off of Instacart, we saw an odd selection under bottled waters.

“What is that?” I said.

“Who would ever order it?” D wondered aloud.

I already had it in my cart.

I fully expected it to be a caffeine, açaí, and hemp concoction, or whatever. But no!

Instead it’s plain water with a mission, which is to stamp out plastic containers. And thirst.

“When a group of teenagers set off into the woods for a weekend of drinking regular water in plastic bottles, they became haunted by an aluminum can of mountain water that was dead set on murdering their thirsts and recycling their souls,” the back of the can reads.

“Once cracked open, no thirst is safe from Liquid Death. After ritually dismembering its thirst victims, this brutal can of water used the severed body parts of dead thirsts to build itself a flesh suit which it used as a disguise to get a job in marketing. But Liquid Death never took the job. it just murdered a bunch more thirsts instead.”

I don’t know who is behind this product, but they’ve got a new fan for life.

I wonder if they know they can name themselves “aquatists” and call it a vocation?

This is so funny. Those liquid death cans have become super popular at concerts and music festivals -- they quench your thirst and they’re not refillable for only $10 a pop!

I'm dying here!!!! LOL! Fabulous, Marjie. I have an urge to send you an EpiPen!! :)